Bad Bunny, Live from Coachella Valley

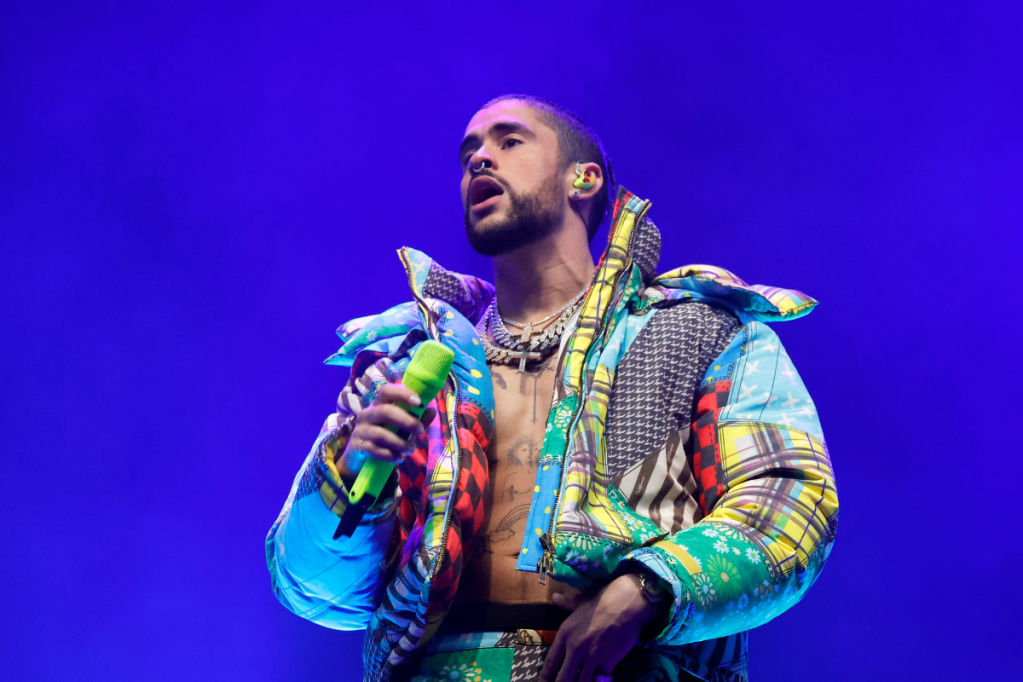

The night was hot. It was 10:45pm as I crested the hill facing the Main Stage, a platform strip like an aircraft carrier jutting out from three enormous screens. From where I stood, performers would look like ants, so far away that the details were lost – but even from this distance, the field was packed. The churning crowd stretched endlessly around me, a sea of festival goers brimming with energy. This was Coachella in all its glory. I checked my steps – 10 miles – as I remembered the richness of the day: the stages, the music, and all the beautiful people. It was heaven. But now, I was dehydrated, covered in dust, and brutally sober. The incoming headliner was someone I hadn’t paid much attention to, so I resolved to sit this one out, massaging my tortured feet. That’s when the lights went out, and the crowd erupted into a deafening roar. Bad Bunny was here.

First, a simple beat – the crowd collectively held its breath – and a cascade of sound tore through the fields, basslines shaking the ground in rolling waves. Then, something strange happened. My exhaustion lifted like a spell, and suddenly I was moving – walking, jogging, then sprinting towards the stage. It was like I was being pulled into another dimension, all saturated lights and tropical melodies. Before I knew it, I was in the heart of the crowd, surrounded by strangers who regarded me with the same wild energy I felt. Bad Bunny commanded the stage, taking us through a labyrinth of sound: tangled and complex one moment, simple and brooding the next – all of it irresistible. I had no choice but to dance.

Just when it seemed over, the music dying down to reveal the crowd’s ragged, sweaty breaths, his baritone boomed over the fields: WHO WANTS MORE PERREO? I didn’t know what the hell that was, but I was right there with the crowd demanding it. This was Bad Bunny – a name I’d heard in college, his music in every car, dorm, and party. Bad Bunny, the upstart from Puerto Rico on a tear, now headlining Coachella. Bad Bunny, the man who, just that morning, I would have sworn was mainstream schlock but turned me into a fan with a single beat. Bad Bunny. Who the hell was this guy?

Bad Bunny, Crown Prince of the Mainstream

As soon as I got home, I dove into his discography. I couldn’t believe what I found: six chart topping albums in just four years, billions of streams, and versatility that shattered expectations. This guy blew mainstream out of the fucking water – and I don’t mean that in a bad way. He was popular because he was just that good. With each relisten, he cemented his place among my favorite artists, his music drowning out the protests of my inner contrarian. It wasn’t all one-note either – each project he put out had a completely unique personality. From the paradise dreamscape of Un Verano Sin Ti to the broiling punk-adjacent road trip of El Ultimo Tour Del Mundo, Bad Bunny showed that his fame didn’t bloat him; it emboldened him to evolve his sound. And yet, through all the experimentation, he maintained a consistency his fans could rely on: his sonorous voice, pristine production, infectious beats, and an overall world-class attention to quality.

If you think it’s too good to be true that one man is behind all of these hits, you’re absolutely right. Even Spotify’s notoriously shallow credits list a dozen producers and writers on every track, not to mention the strategically selected features on his hottest tracks. Bad Bunny is a figurehead on an enormous industrial music machine. It’s important that we acknowledge the hundreds of nameless individuals who helped propel him to where he is now. The critic in me wonders how much of this is his talent and how much is The Machine – but the optimist reminds me of what I know to be true: His music has inspired millions. His music can be enjoyed unapologetically – just with a healthy side of salt.

Bad Bunny, Trailblazer

Bad Bunny was an incredible starting point, but he quickly became my gateway to something bigger. Through his vast collaborations, he revealed a world of Latin music of which I had barely scratched the surface. Artists like Yung Miko and Rauw brought hip-hop reggaeton, Grupo Frontera delivered sorrowful corridos, and The Marias and Judeline revived a bedroom pop sound that I thought I had left behind. Bad Bunny didn’t just open up a world – he unlocked a universe, each artist a new star with a unique story to tell. I was hooked.

While exploring music from other cultures has been undoubtedly rewarding, there’s also a steep learning curve in navigating the space between genuine appreciation and shallow tokenization. For one thing, my limited grasp of Spanish adds a thick layer of distance – until I achieve fluency, there’s an intrinsic gap in my understanding. On a deeper level, for all the pride that comes with discovering something new, I sometimes feel a nagging discomfort – like I’m a tourist wedging myself into a world I don’t belong. Even as a fan of several years, my admiration sometimes feels countercultural rather than authentic. Artists like Bad Bunny have done incredible work in decreasing that discomfort, introducing the unique sounds of Latin music to the mainstream, but the work is far from over. He’s done his part to bridge the gap – what we do with that is up to us.

Bad Bunny, Masculine Ideal

Reggaeton and hip hop have long been rooted in hypermasculinity and machismo. These genres celebrate the objectification of women, wealth and excess as markers of masculinity, and violence as a solution. Make no mistake – Bad Bunny explores these themes plenty – but one quality sets him far apart: Bad Bunny is fruity. We’re not just talking bright colors, heeled boots, or painted nails (all of which are regular parts of his image), we’re talking full drag in one of his most popular music videos and a declaration of sexual fluidity. He wants the world to know who he is.

High School was the first time I really grappled with sexuality and masculinity. It was a volatile time – my identity felt like clay, shaped by everyone around me. I was on the wrestling team which was physically very gay but mentally very hypermasculine. I was also in choir and theatre, where I was bombarded with the dual-messaging of “all theater kids are gay” (true) and “women love a man who can sing” (also true). I dated girls, but something about it always felt incomplete. It wasn’t that I liked boys exactly – it was that I didn’t want to narrow my options. I didn’t know if I’d someday like men – or if I’d always want to be one.

Despite this uncertainty, I told people I was straight. It was a convenient second choice – I didn’t feel like it was my place to declare an identity when I didn’t even know what it was. Years later, learning about Bad Bunny’s casual approach to sexuality felt like a puzzle piece clicking into place. He embraced a masculinity that made room for fluidity, unapologetically blending strength and softness I’d never seen someone so famous represent the middle ground, and he did it so confidently, solving my years-long struggle with a shrug. It feels ridiculous to say that a reggaeton megastar made me feel seen in my queerness, but we don’t choose our absolution. For me, it was Bad Bunny.

Through his music, Bad Bunny explores these ideas, challenging traditional notions of men in his position. He balances the dark roots of his genre with the promise of a more nuanced future. Songs like Safaera and Yo Perreo Sola are aggressively and lewd – diabolically horny – but they carry an undercurrent of appreciation and consent. His lyrical style doesn’t align with my own sexual tastes, but I can’t deny his impact; many consider his approach to sex liberating, progressive, and even revolutionary. In Titi Me Pregunto, he reflects on his own toxic masculine tendencies with a layered self-awareness. He opens with a tirade of sexual braggadocio, literally listing the women he’s slept with – only to transition to a devastatingly reflective resolution, I hate myself more than you hate me. Through his music, he’s carved his own masculine image – not through performative allyship or trite PR, but by simply being himself.

Bad Bunny, Pride of Puerto Rico

If there’s one thing Bad Bunny makes clear, it’s that he’s Puerto Rican. From the lyrics to the beats to the features, he layers his cultural background into every aspect of his work. He celebrates its beauty, drawing inspiration from its traditional sounds, while also confronting its struggles and the scars left by colonization. His most recent album is his most culturally inspired work yet – Debi Tirar Mas Fotos is a love letter to Puerto Rico, blending the energy of a dance party with the gravity of social commentary. My favorite track, Turista, is a heartbroken lament about the effects of tourism on his home. Before him, I barely knew where PR was on a map. Now, the whole world is singing its anthems.

As a Filipino, my identity feels layered and complex. My culture is a mix of Latin, East Asian, and American influences, no small thanks to centuries of colonization. Sometimes it feels like I’m less Filipino and more a mix of everything else – a culture pieced together from borrowed parts. Personally, I’m proud of my culture. I know Filipinos have done great things throughout history; I know we have an identity. But it doesn’t feel strong. It sometimes feels like we’re irrelevant – a tiny island nation that doesn’t bring much to the cultural conversation. Sure, we have Olivia Rodrigo and Bruno Mars, but we sure as hell don’t have a Bad Bunny.

I wish I had something strong to say here, a bold declaration of pride and hope for my culture’s future – but I don’t. Reflecting about Bad Bunny’s pride in Puerto Rico made me think about my own culture, and it left me feeling small and sad. That’s a personal journey that I need to work through. Maybe Bad Bunny felt the same way about his tiny island nation. Maybe he was just as frustrated as I am now.

Bad Bunny, A Million Things

At the time of writing, 86 million people are listening to Bad Bunny on Spotify – a staggering number, and one that shows no signs of slowing. He’s huge, and he means a lot to a lot of people. No two perspectives are alike – some are deeply invested acolytes, while others, like me, are more casual fans, passively inspired by his message. But with fame that massive, a lot of nuance gets erased. Bad Bunny – and his fans – have become part of a cultural monolith. Sometimes, when I tell people that I’m a fan, I feel the need to add qualifiers, like condiments on vanilla ice cream. Yes, I listen to Bad Bunny, but… has become a regular part of my vocabulary when discussing music and culture. Everyone knows what he is, so nobody cares who he is.

On the other hand, trying to cut through the surface is an exercise in futility. I could research as much as I want, but at the end of the day, nobody can know who Bad Bunny really is behind the curtain. And frankly, that’s perfectly fine. He’s shown me new music and cultures. He’s answered questions about my identity and prompted me to ask new ones. What more could I ask? If anything, my experience with him validates the ambiguity of my own identity – both are layered, unresolved, and open to reinterpretation. Bad Bunny doesn’t need to be defined. His art invites us to see what we want, take what we need, and let the rest remain a mystery. For me, that’s been more than enough.

Leave a comment