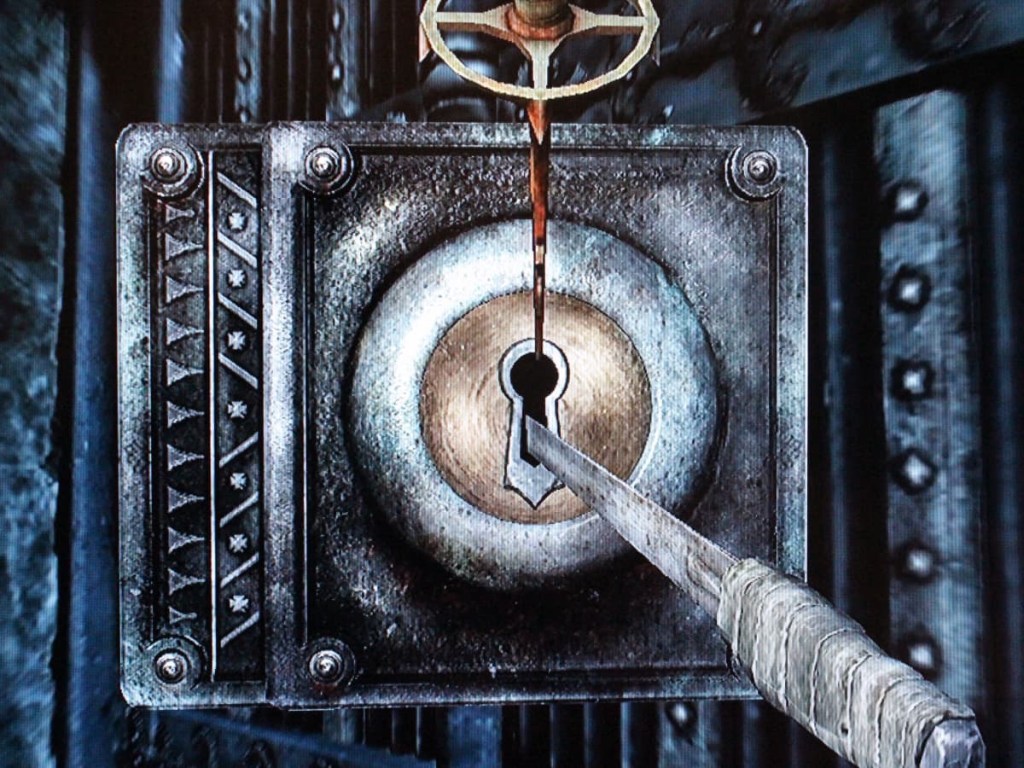

The clock strikes midnight – you shift from shadow to shadow, the only sound the muted rainfall against the manor’s stained-glass windows. Lord Scurlock should be fast asleep – it’s the perfect time to take what’s yours. The door to his infamous study looms before you. You gingerly turn the handle, but it doesn’t budge. Of course. A sophisticated lock system for a sophisticated bastard. You pull out your lockpick set with a flourish, you roll to break in, and… you fail. What happens next?

In TTRPG, failure can be a real bummer. For players, it’s a letdown when your character fumbles. For GM’s, choosing the right consequence is a creative challenge that, if met with hesitation, brings the game to a screeching halt. The thing is, we need failure and consequences. For a story to be a story, heroes need to be challenged, to learn from setbacks and mistakes. How can we make this a welcome part of our games? How can we not only integrate but welcome this vital narrative element?

Why DnD’s Failure System Failed Me

Like many GM’s, my experience with failure/consequences in TTRPG begins with DnD 5E. Unfortunately, the game does very little to help new GM’s with this concept. The DMG (pg 237) states that, if a player fails a skill or ability check, they can simply try again, the only consequence being that it takes (specifically) ten times longer on a second attempt. In that case, the intuitive next steps are as follows:

- Other player characters in the group attempt the same roll

- Players attempt a different roll

The first case is the worse of the two. Not only does it take the spotlight off the character who attempted the roll first, but it also leads to a very stale sequence of play. There’s something sad about players going around in a circle trying the same thing until someone gets it right by pure chance. The second case presents a more promising narrative progression but can also feel overplayed when done too much. Either way, both cases often take an inordinate amount of real-world time to resolve, wrecking narrative momentum.

The DMG touches on this a few pages later (pg 242) with a section on other approaches to failure: success at a cost (you succeed but a new problem emerges) and degrees of failure (the quality of your roll determines the severity of the consequence)1. It includes some examples which are admittedly quite helpful, but I take issue with a few things:

- It’s a tiny section in the DMG that most players will never see

- There’s no system for how to curate consequences for failure

- The section is treated as entirely optional!

For something so essential, this is not nearly enough. My mission isn’t to trash on DnD – I love it for what it is, and any GM can learn to intuitively rule failure/consequences with enough experience. That said, the vast majority of TTRPG players start with and even exclusively play DnD. I was once that player, and it’s inspired me to write this piece. For those like me that once struggled with failure and consequences, I assure you there is a better way.

A Narrative Approach to Failure and Consequences

Enter: Blades in the Dark. This is one of my favorite systems precisely because it addresses the consequence/failure issue with such elegance. When I played it for the first time, I felt something click in my head – I wasn’t just learning rules for a system. I was learning rules for storytelling. BitD fundamentally shifts failure from a dead-end into a storytelling tool. Instead of blocking progress, a failed roll introduces a twist – one that adds tension, drama, or a new challenge to overcome. It goes something like this.

You roll to pick the lock and fail:

- Reduced effect: The door is stuck halfway – just enough for smaller members of the crew to fit through, but not everyone

- Lost Opportunity: You’re about to pick the lock, but you hear a spectral guard coming around the corner! You have to hide – fast.

- Harm: Your pick triggers a trap which sprays a blinding acid in your face

- Worse position: The door opens, but a timed alarm sets off. You have seconds to disarm it or the whole manor wakes up

- Complication2: You open the door to find another crew with their hands on the lockbox – what happens next?

This framework accomplishes several things at once:

- Ensures a clear next move: Instead of the lockpick just not working, a new opportunity/threat emerges, discouraging repeat rolls3

- Honors the characters: The partial-success nature of these consequences portrays the PC’s as skilled and capable in almost every situation

- Encourages action: The partial-success nature of these consequences gives players a reason to act boldly instead of hesitating

Cause and Effect

The most foreign element of this system is the source of the consequences. Instead of a strict cause-and-effect (you fail to pick the lock, so it breaks), BitD encourages you to lean into a broader narrative causality. Failure spawns new problems: you fail to pick the lock and guards happen to turn the corner; a rival crew happens to be waiting on the other side. These obstacles would not have existed without a failed roll, and that’s okay! The system prioritizes telling the most interesting possible story; by presenting you with options that are guaranteed to raise tension and stakes, all you have to do is fill in the blanks and let the bad times roll.

Making Failure Work for Your Story

As much as I love this system, it absolutely does not work for every situation, or even every table. Telling a good story requires a sensitivity to how these consequences fit into the tone and theme you’re trying to convey. The BitD system naturally fits for fast-paced thrillers with stakes that build until they break. That can get very exhausting! Sometimes, a situation calls for the puzzle room style; a more relaxed scenario where players can try options without fear of immediate backlash. That’s why I encourage GM’s to try as many systems as possible; you can learn from each of them, adding the best bits to your toolbox as you go. The most important thing is to set expectations for what consequences will look like at your table. After all, you’re telling the story together. Agreeing on the stakes is a priority, so that – win or lose – everyone’s having a great time.

~~~~~~~~~~~

So, how do you deal with failure and consequences in your games? What’s in your toolkit? What other systems would you recommend? Let me know in the comments, thanks for stopping by!

- This section also includes the massively more memorable critical success/failure system, which is also optional! Interesting to see what the culture chooses to adapt vs ignore. ↩︎

- This consequence is a little redundant to me and presents a potential area for streamlining within the BitD system. It’s nice as a catch-all, but a little clunky. No system is perfect! ↩︎

- Does this mean you should never re-roll a skill? No. For me, re-rolls are okay as long as consequences change the status quo before a player rolls for the same check again. ↩︎

Leave a comment