I wake up before dawn to run. Bitter cold, howling wind, pouring rain, and darkness – hundreds of miles to become stronger, stronger, stronger. The past few weeks have been a constant battle against pain; shin splints, microtears, dehydration headaches, cramps – I’ve never felt so much like my body is falling apart. In just a month, I’ll be running the LA marathon, but until then, I’m fighting a quiet, internal war.

I didn’t just wake up and decide to run a marathon. I don’t think anybody does. For my part, I’ve always loved distance running: the fresh air, the runner’s high, the meditative aspect. So, with a couple of half marathons under my belt, I figured I’d take it to the next level. I knew that you couldn’t train for one of these without seriously pushing your limits; extreme distance requires extreme dedication – but nothing can prepare you for the reality. When you’re in the thick of it, it’s all you think about.

I didn’t seek out extreme media, at least not initially. It kind of just lined up with my mindset. I was always aware of its existence on the outer edges of my perception, but it wasn’t until I started testing my own extremes that I began to notice it everywhere. Pain, endurance, obsession – the further I pushed myself, the more I saw those same instincts reflected in places I hadn’t thought to look. People pushing their minds and senses, rather than their bodies. People who sought out not just the beautiful, but the unbearable.

I started paying attention.

Noise

I first came across the noise genre a few months ago in the comment section of a subreddit; a joke poked at the genre’s unlisten-ability, which I immediately took as a challenge. I flipped over to Spotify and threw on a track, and within five seconds I was scrambling to pull my headset off. I felt like I had heard hell itself, a wall of sound so repulsive and jarring that I didn’t dare press play again. Naturally, I shared it with all of my friends.

Text: “Headphone warning, volume warning. Tell me how this makes you feel”

Responses:

- “Upset”

- “Someone definitely got stabbed to this”

- “I think I went into fight or flight.

- “It was not soothing to my ears”

- “Who would listen to this on purpose?”

My friends described the music as overlapping screams, tv static, and even nails on a chalkboard. That said, those descriptions do little to capture the experience in any detail. There’s clearly some complexity beyond the initial shock – What exactly is noise, as a genre?

Music, typically, is a combination of several aspects: harmony, tempo, dynamics, melody. Noise removes those aspects that are the most comforting; you’re left with a sheer soundwave of timbre, texture, and pitch. Artists with particularly niche voices find a platform in this strange sonic frontier: you’ll find a selection ranging from the avantgarde (Woodpecker No. 2, Imaginary Creaking) to the profane (SUFFER FOREVER, Extreme Headache Gorenoise). This deconstruction of music as we know it lends itself to the exploration of new ideas, new extremes. I really respected that. I was ready to try again, but this time, I needed some direction.

I dove into the relevant forums and was inspired by what I saw; The noise community is alive and well. Artists produce a steady stream of new tracks, which are met with resounding praise. More than that, it’s strongly encouraged that fans learn how to produce noise, further enriching the community. Several underground venues actually host live shows; these are central to the subculture and act as an important meeting place for its fans. It’s good to see that the culture is supported by such generosity, inspiration, and warmth. However, even with such a robust following, I found no definitive answer as to why people loved it so much. The truth became clear – I just had to dive in and see for myself.

Pulse Demon – Merzbow1

In my search for the perfect introduction to noise, dozens of recommendations pointed to one album: Pulse Demon by Merzbow. Merzbow’s prolific career as a noise artist began in the early 80’s. Inspired by surrealist art and dadaism, he utilized live industrial electronics to push the limits of music itself. I was especially surprised by his use of music as a platform for activism. Much of his work is deeply tied to environmentalism, animal rights, and anti-capitalism. Even now he’s one of the foremost artists of the genre, producing dozens of projects every year, each a bold statement in its own right. Fantastic resume notwithstanding, I was still hesitant – my first impression with the genre wasn’t so easily forgotten. I settled into my chair, prepared myself for the worst, and hit play.

The first thing I felt was pain. The sound was absolutely disorienting, a car crash of shrieks and sonic tears. That first song, Woodpecker No. 1, was the hardest by far. It was a deeply distressing tirade of unrelenting noise that, at seven painstaking minutes, took its sweet time. It wasn’t unlike being thrown into a moshpit, the various sounds shoving me around without mercy, but I stuck through – I was determined to understand. I focused all my energy and listened. That’s when the skies cleared. Timbre, texture, pitch – there was a method to the madness.

The longer I listened and the more I focused, the more I could see the throughline. It became clear that Merzbow was using a (surprisingly sparing) sonic palette, deployed in sequence such that you can hear intentional changes in the sound. Sure, it was chaos, but it was cherry-picked chaos, selected to taste. Once I got over the fear, it almost felt like a sampling plate, each cadence a “bite” with completely new flavor.

While 90% of the album was continuous sound, there were a few moments of silence and lower-pitched reverb that played an enormous role in breaking the experience into parts. Because of that, I actually came to recognize – and even appreciate – the personality of each track. To that end, at just over an hour, the album didn’t overstay it’s welcome (a conclusion I came to only after deciding it was welcome at all). This was a focused effort to communicate his passion, not at all the obnoxious exercise in drawn-out suffering that I imagined it might be. Clearly, Pulse Demon was the product of unbelievable love and care.

The question is, did I like it?

Here’s what I can say. As soon as the album finished, I sat in silence for five minutes. Then, I put my headphones back on and I started from the beginning. I sat through another full run-through, and the next day, I put it on again. I don’t think I’ll ever believe that Pulse Demon – or any noise music, for that matter – is beautiful, relaxing, or pleasant. However, I can say that it did something for me that no other music had done before. Usually when I listen to music there’s a visual, a feeling. With noise, I thought I might get disorienting, chaotic, or even violent thoughts, but it instead had a numbing effect that wasn’t unpleasant. Pulse Demon filled the gaps in my thoughts in a way that was almost meditative. It prevented me from thinking too much, which, although done by force, was an enormous achievement.

After Pulse Demon, I started to hear noise everywhere. The echo of my toothbrush in my mouth, the construction down the road, tires on asphalt and birds calling to the sun. We’re constantly surrounded by noise, and if we can train our ear to hear noise as music, then life takes on a strange and beautiful new shape. Against all odds, I had found merit in something that was previously unbearable. I wasn’t sure if that was a good thing. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to find out what else I could get used to.

Gore

WARNING: Graphic descriptions of violence

Return readers will know that horror movies are my favorite. The heightened stakes, the breadth of material, the character studies – all are such unique elements that bloom in the genre’s fertile soil. That said, horror without nuance has always felt, at best, pointless, and at worst, gratuitously sick. I’m talking about gore. I always saw movies like The Human Centipede, Cannibal Holocaust, and the later Saw films as paper-thin; Ars gratia artis drenched haphazardly in blood and guts. However, my foray into noise music had imbued me with momentum and curiosity. Was it possible to find meaning in extreme violence?

Due to its rich history with the material, I decided to root my exploration in Japanese gore (and also because Merzbow is also Japanese and I thought it would be cute to have a theme). Since the 70’s, Japan has been a leading influence in the genre. Its dominant culture of sterility gave way to an intense counterculture of extremity, which extended into its music, fashion, and film. These movies aren’t afraid to get very, very messy. Japanese gore at large tends toward the surreal and experimental. House (1997, Nobuhiko) is art-house gore with a dash of comedy; Audition (1999, Miike) has an intensely gory climax but leads with a dreamy aesthetic. Japan’s mastery of the visceral even extends across genre – mainstream anime like Attack on Titan and Demon Slayer incorporate extreme violence to great effect.

Underneath the surface, however, was the real shit. Entire reels dedicated to pure suffering: boiling oil basted across skin, bodies hung from meat hooks, entrails pinned to walls. I had a lot of options, but there was one series so wicked that I had never even thought to touch it. A perfect, gristly, starting point. Pandora’s box was open – I just had to look inside.

Guinea Pig 2: Flower of Flesh and Blood

The Guinea Pig series is a set of six films that explore physical suffering from every angle. Guinea Pig 2: Flower of Flesh and Blood (1985, Hideshi Hino) is the most infamous of the bunch; the name alone sends ripples of whispers throughout the horror community. According to legend, it was so realistic the Japanese government brought Hino to court, demanding he prove his effects were fake. On top that, this movie was said to have influenced the Otaku Killer, a serial killer who kidnapped and dismembered children in mid-80’s Tokyo. While this was largely debunked, the story lives on. Flower’s reputation preceded it by far.

The movie goes like this: A guy kidnaps a girl. He ties her to an operating table and injects her with a serum that turns her sensations of pain into pleasure. He proceeds to dismember her: hands at the wrists, arms at the shoulders, legs at the waist, and finally, a beheading. All the while, the serum takes effect – she feels nothing but ecstasy, barely stirring as he hacks her into bits. He cuts her stomach open to remove her entrails, and then he takes a spoon to scoop out her eyes, which he sucks on with gusto. Finally, he takes her body to his “garden”, a decorated area of patio furniture and plants where he juxtaposes the body parts, as if arranging flowers. The movie ends with a similar shot to the beginning, trailing another unsuspecting victim. The cycle continues.

The experience of watching Flowers was not at all what I expected. I was so scared to watch this movie that it took me two weeks to put on. When I finally pressed play, I felt a rush of lightheadedness, and as the torturer reached for the knife, I felt my palms clam with sweat. But then, the serum. Wait a second. If she wasn’t gonna feel any pain, then what was the point of the torture, and by extension, what was the point of the movie? I figured it would center on the woman’s suffering, but no, she was just a placeholder, an incidental prop in the performance. The woman wasn’t the subject – I was.

The suffering was mine and mine alone. While she slept through her deconstruction, I was the one squirming, dreading, waiting for the next cut. Flowers of Flesh and Blood is an exercise in fear itself, weaponizing our own anticipation for a completely unique watching experience. Indeed, the process wasn’t torture so much as a ritual, executed with a sense of beatific reverence vs masochistic hedonism. The movie asks, what is the connection between empathy and suffering? What is violence without pain? As realistic as the effects were – and they were really realistic – they shy in comparison to the horrors of our own expectations. A knife held gently against unscathed flesh has more weight than all the dismembered limbs combined.

Even with this revelation, the question stands: why engage with such violence in the first place?

Media is bloated with the maximization of ideal beauty. This makes for a safe ecosystem, but one that lacks range. Life is about experience, and if we limit ourselves to the beautiful, we deny ourselves contrast. By delving into the deep end – by occasionally confronting what horrifies us – we sharpen our understanding of beauty itself. In Flowers of Flesh and Blood, each incision was a reminder of my body’s fragility, but also its wholeness. To safely witness total destruction was a powerful experience – horrifying, yes, but meaningful nonetheless.

I’m not coming out of this a fan of gore. If anything, I’m relieved to close the door on this experiment – and even more relieved that I didn’t uncover a perverse affinity for such violence. However, while I won’t be revisiting this violent world anytime soon, I know it will always be there: a reminder of what can be taken and what remains.

At the Edge

I went into this experiment thinking that noise and gore would be virtually the same: a purely overwhelming experience made only to repulse. Instead, I found a rich and complex world of artistic value and expression. Pulse Demon demands complete immersion – the only way to find the patterns is to bury yourself in the material. In contrast, Flower of Flesh and Blood is a masterclass in meta-horror, strangling you with fear before the movie even begins. In retrospect, I feel a little silly for thinking they’d be the same. They’re extremes within their respective genres – naturally, they’d make for extremely different experiences.

And yet, there’s a shared heart: The discovery of beauty through the medium of extremity. Noise and gore are exhausting, yes, but they show us the full spectrum of human experience – there is no good or bad, only contrast. They demand the use of muscles untrained: scrutiny and perspective born from fear and unfamiliarity. Pulse Demon reveals the beauty that’s always there; sound in any form is a universal expression of identity itself. Flower of Flesh and Blood reveals beauty in sharp relief, baptizing you in viscera to remind you of things taken for granted.

As I’m writing this, I get up every 30 minutes to stretch my torn-up legs, to massage blood into them that I might heal. I’m running 20 miles tomorrow. It’s my longest run yet, and I know it’s gonna hurt for days after. People have asked me why I’m doing this, and it wasn’t until I explored extreme media that I found the answer that I had known all along:

I’m running a marathon just to see.

For me, the race isn’t about the finish line. It’s about the miles in between – the push, the challenge, the unknown at the edge of my limit. Extremity strips me down. What remains is raw, undeniable – the beauty of what’s real.

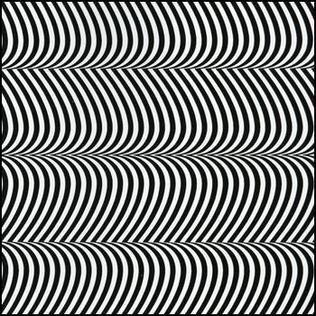

- The design at the top of the post is Pulse Demon’s album art! It was actually made by Merzbow’s wife, Jenny Akita, who designs many of his album covers. I think it’s perfect – it looks exactly like how the album sounds. ↩︎

Leave a comment