Here we have our first guest post! My sister wrote this one. I love her and her writing dearly. It’s about packing, control, Tetris, and limitations. Enjoy.

I frequently worry about space and limitations. “How much time do I have to complete this task?” “Is there a weight limit for what I can bring?” “Can I offer more than one response to this question?” I cringe thinking of finiteness: chances to correctly enter a password; time-locked electronic submissions; space occupancy restrictions; rigid yes’s and no’s.

As the type of traveler who spends hours poring over what to pack on trips (whether long or short), I never truly complete the task of packing until the

final panicky 10-15 minutes allowable before it’s time to leave. In the weeks before a trip, my thought process goes as follows: “Meh, I probably have

everything I need; therefore, I’ll know what to bring when the time comes; if I forget it, maybe I’ll just buy it when I get to our destination.” After all: isn’t it so much more tolerable to simply buy an item you can’t find (even though you most likely already have it), because you either don’t want to look for it, or simply do not have the time (or literal luggage space) to obtain it? My Google searches before an international flight are habitually filled with frantic, typo-ridden, duplicate queries about the TSA’s volumetric and weight limits- anxiously “just wanting to make sure” that I have carefully and correctly accounted for each essential in such limited space, literally and figuratively weighing which ones are worthier of occupying it. What actually ensues: a cyclone of pacing and snap decision-making under the time pressure, exasperated from analysis paralysis. A last-minute stuffing of “just in case I need them” items force me to push my entire body weight on my bursting luggage. And then, there is the most Herculean task: attempting to close my luggage zipper, tooth by tooth, to avoid producing its otherwise obnoxious crescendo as it struggles to close, so as not to stir the rest of those catching a few more moments of sleep. Perhaps being an over-packer makes me a dependable traveling companion, the perpetual carrier of forgotten but necessary items (like charging cords, antimicrobial wipes, Q tips, or chewing gum). Paradoxically, however, I am guilty of being just as much an under-packer, running out of many essential toiletries mid-trip multiple times. A recent de-cluttering of my belongings exposed just how many of sheepish purchases of overpriced toiletry duplicates I’d made, hiding in the backs of multiple cabinets, forgotten from the packing list (and probably doomed to be forgotten again), perpetuating my obnoxious cycle of overconsumption with each new excursion.

Space and limitations in my childhood did not ‘exist’ past the childlike imagination until I exhibited difficulties with Remembering Things – forgetting my lunch box, homework, and permission slips countless times. Even today as a grown ass adult, my limitation of struggling to Remember Things (like my professional identification badge or even passport) continues to be a challenge. I often daydreamed (and continue to daydream) about hammerspace

(“the fictional concept that one can pull seemingly impossible objects out of nowhere” [Spider-Man, Into the Spider-Verse 2018]), resolving this ongoing

problem. As a compensatory mechanism, I have fallen into a habit of being The Girl with the Big Ass Bag, unwilling to be away from my laptop at any

point in time. This creates the inconvenience of needing to carry it around with me everywhere in the Big Ass Bag (which most colleagues have come to

associate as an extension of me as a result) because of this deep-set fear of being unprepared and therefore ‘limited’, incompetent, or useless.

My perceived limitations as a form of what I’m Willing to Do have heavily informed what I have the ‘space’ to do. There is a comical disparity in my

threshold to execute certain tasks, rarely batting an eye in performing surgeries that require millimeters of precision, but panicking from merely seeing a heap of unfolded laundry. Even the mere thought of cooking—a necessary task for human survival—has been debilitating. I am ashamed of how much mental energy and space this task demands of me. It is somehow far more ‘impossible’ to complete the Sisyphean task of deciding what to make and eat each day, with the overwhelm of carving out a time to drive to the local grocery, pick out ingredients, remember all of them for a meal, and not get distracted while performing every step in preparing it; the thought of dripping sauce, dirty dishes, and mountainous wares filling my sink yielding me incapable of doing anything about it. My meal prep era? Horrific. With my professional/academic ‘plate’ stacked with tasks like preparing for dental boards, studying for licensure exams, and completing patient prostheses in lab, and my personal ‘plate’ piled high with interpersonal or mental health challenges, I often came home too late to cook. Paradoxically, I would overbook my weekends with a part-time job and social events to create more limited space to then force myself to study (i.e., cram with such self-imposed stressors), which often led to being unable to cook for the week; organic ingredients rotting away as their deterioration outpaced my analysis paralysis and sheer forgetfulness. A ruthless cycle of not knowing how or why I had so many distinct, excessive volumes of ingredients that I would truly only use one time for one recipe; forgetting which items we had already bought and occupying more space with their duplicates; wasting and wasting and wasting, over and over again, and buying and buying and buying to compensate, was absolutely exhausting. At that point, the seemingly more cost-effective meal prepping was becoming more wasteful. “Let’s just get takeout,” I’d often tell my husband when asked what to eat for dinner.

With all this, perhaps I am fortunate (and in a way, handicapped? #noablism) to live in a time of convenience culture, which, through a few touch screen

taps of instant gratification, has literally virtually eliminated most of the aforementioned ‘problems:’ I can just buy more pairs of scrubs to minimize how frequently I need to deal with the laundry; I can just get food delivered when I want it without needing to prepare or think about when or how I will eat in advance. These ‘tasks,’ like getting new clothes or a fresh meal on command, ‘live’ in my phone, and magically appear at my doorstep. Through an

optimization lens, such conveniences free me to accomplish so many other tasks in the time it would otherwise take me to perform the menial ones.

Through a sustainability lens, I end up taking up more space, utilizing more resources, and contributing more waste as each randomly ordered parcel

arrives with redundant plastic and cardboard packaging, refilling my trash receptacle and thus ironically creating another menial task of taking it out in my attempt to avoid the others.

My recent trip to Japan was truly a case study in space utilization, whether virtual, physical, or mental. The sheer amount of space my Google Photos

carry, coupled with the fact that I had somehow managed to accumulate enough information to take up all of its available space, led me to make a

decision out of a self-perceived limitation balancing costs and payoffs: in the time that it would take for me to delete redundant or unnecessary photos or videos in my photo library for the sake of making more space, I could simply…not do that (too much work), and instead, choose to take on the budget-

friendly monthly cost of $4.99USD to simply acquire more space (2 TB to be exact). How convenient! Instead of fitting within limitations, why not just

push them further for one’s own means? In contrast, the efficiency and expediency of Tokyo’s public transportation system is a modern miracle and

genius utilization of space; creating rather than consuming, innovating the capacity despite various limitations to support the needs of its millions of

inhabitants in one of the most globally recognized, densely populated cities. Because millions of folks from the Kanto region (a much smaller geographic

area than California), are able to travel to work, school, violin lessons, or bring groceries home on a single public transport system, only a few vehicles

are necessary to occupy the roads at any given time; something unheard of to an LA native. As a tourist, I viewed Tokyo’s public transportation as a

procrastinator’s dream, wherein missing the train to a given desired destination had no more than an approximate six-minute wait time for the next one, also headed to that destination. It was also, in contrast, a claustrophobic’s nightmare: inhabiting a shared space with the just as efficient, expedient locals and their unwavering willingness to squish, cram, and make their personal space and comfort smaller and smaller to make more of it for others.

Collectivist, capitalist, consumerist, and insanely fucking cute, Japan’s soft power really had me folding for each and every one of its goddamn beautifully packaged products (“Japitalism,” or Japanese capitalism, as coined by my husband). No item was left unturned; all were fair game for stuffing our empty

check-in bag on our journey back home. I was astounded at the seemingly endless inventory of products I never thought I needed, all within such limited space! Needless to say, at the end of the trip, my poor husband was carrying both of our densely packed, enormous check-in luggage bags on the way home.

Since this trip, I have also meditated on the non-physical non-quantifiable aspects of limitations; the imperceptible, abstract, and mental: throughout my decades of being a student, my disorder of inappropriate focus has been one of my biggest limitations. Yet, in many ways, I have begun to reframe this

quality as a superpower, fondly reminiscing about the early days of dental hygiene school, attending classes three rows from the front (an absurdly

ambitious position for halls that sat 200 people at minimum). Like a court reporter, I could deftly document what professors said during their lectures in the form of beautifully detailed notes at an average typing speed of 120 wpm. By exam season, my lecture notes were in high demand by classmates

who had made a habit of ditching class, desperate for more context than whatever our anemic Powerpoints provided.

Eyes glued to my laptop, fingers flying, what most were often unaware of was that I was not truly typing each word spoken by our professors, but playing

Tetris Free online.

[In fact, the detailed notes in question were usually just typed at home when I really had to study, documenting whatever my phone recorded from the

live lectures I attended [with our professors’ consent to record them, of course]). One might ask, why couldn’t I have just typed the notes live in lecture, if I was so damn good at it? Because, of course, despite it being an optimal approach to making more space for myself to be a person and not a gremlin-like procrastinator, I was limited by the lack of urgency to take care of it—anything intolerable, uncomfortable, being ‘too difficult’ until the time arose.]

Tetris (yes, the game) has occupied my headspace since I developed a benign addiction to it at least half my life ago, and even more recently as a

concept in general since my brother gave me one of my favorite compliments ever (“being good at tetris is one of the coolest things about you”) The

euphoria of watching each tetromino fall as I guide it into place, allowing me to clear line upon line of accumulated pieces forming manageable shapes;

intentionally allowing an accumulation of stacked pieces to score a ‘tetris’ (a clearance of 4 lines simultaneously with a single piece), has always

incredibly therapeutic. Commonly, unintentionally dropped or poorly positioned pieces (‘mis-drops’) create artifacts of unwanted verticality and voids, generating a non-clearable shape as it hoards precious space. These mistakes accumulate, hampering the player’s ability to maintain the space to

accommodate the ongoing quickening precipitation of more pieces, impacting the present and future of the game. I love learning new, different

techniques to playing the game and how the interplay between physical space and virtual space (i.e., the benefits of certain physical consoles designed

to optimize gameplay) so profoundly shape the course of a game. One feature (holding a piece) lets one save a perhaps more valuable piece for later;

another feature, a display of the oncoming pieces, allows the player to plan ahead and optimize their chances of scoring a tetris. Tetris was my

controlled, fun form of self-imposed stress: despite the progressively quickening descent of each tetromino over time, it helped me self-regulate, think clearly, and focus, especially during my lectures in grad school. It was not only a study necessity, but mental health support; a comfort through various personal traumatic events, periods of depression, and bouts of anxiety. This rote task was just as predictable as it was unpredictable, and best of all, a new, fun experience every time I played it. My sister recently taught me that tetris “helps with trauma,” and she was right: a 2020 cohort study proposes that Tetris “may be useful as an adjunct therapeutic intervention for PTSD” (Butler et al), thought to be preventive in lessening memories of a traumatic event. Future directions for research given these findings: exploring the effect of Tetris on brain structure.

Basically…it’s just really fucking cool.

With that, I’ve been working on reframing my thoughts on space and limitations this season. It has nearly been a year since enduring an arduous, real- life version of Tetris on hard mode: juggling applications to residency; prioritizing my personal physical fitness to manage my mental health; working

through personal loss and grief, medical emergencies; betrayal; matching into residency; studying for, practicing, for, and passing all my boards;

becoming closer to my siblings; graduating from dental school, obtaining my dental license, making and losing many friends; reconnecting with long-lost

soulmates, and now, stepping into a new chapter and decade of life. It is as though I have somehow cleared multiple lines of tetrominos, creating far

more space to take on more of them.

Maybe life isn’t just one big Tetris game, but a sequence of many game attempts to push one’s own personal high score and upper limit; developing and learning different techniques to weather each onslaught of randomly falling pieces, and resolving unique configurations.

Someone once told me that, similarly, life doesn’t get easier: you just get better. In many ways, this has felt to me like letting go of what doesn’t fit

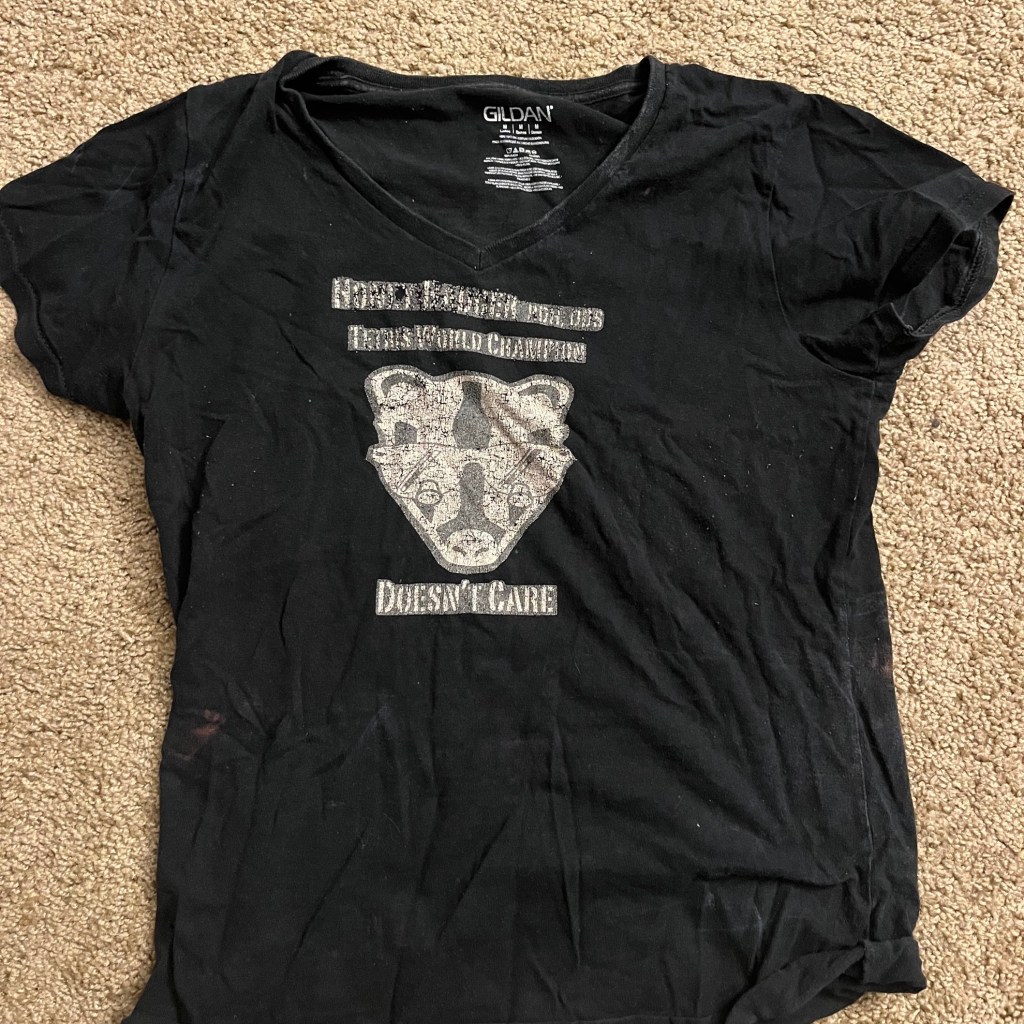

anymore. While decluttering during my move, I recovered a t-shirt gifted to me by a colleague a few years ago: above a large illustration of a honey

badger reads the title “Bella Idea – RDH, DDS, Tetris World Champion.” Though I have never been a Tetris World Champion (not even close), I was also

not yet a dentist at the time of receiving the gift (and wouldn’t be for about 6 more years). I still play Tetris, though sparingly during lectures (having less anonymity as one of 4 residents rather than one of 150 students). Just like taking stock of the developing shape of fallen tetrominos, my reflection on numerous past and future versions of myself, and how infinitely they both converge and extend past the present space I occupy, continues to challenge and inspire me: do I at some point become my full, ‘true’ self, like a finished, definitive sculpture carved out of marble? Or am I the culmination of extensions, artifacts, and branches from a common origin, like a growing tree, or accumulating, uniquely shaped set of descending blocks? Though I have chosen to not to part yet with that now ratty, 6-year-old t-shirt (faded honey badger illustration and all), despite my already limited apartment space, I may indefinitely hold on to it like a found object: proof that a version of me was here, that a version of me is here, and that a version of me will be here.

Leave a comment